Welcome to our page. Please find further publications here:

Translated versions are available:

The reference version is the English one published in The Lancet. Translations are provided for your convenience. Thank you to our volunteer translators.

Your language is not available? Contact us to provide a translation.

An action plan for pan-European defence against new SARS-CoV-2 variants

This statement was originally published in The Lancet on 2021-01-21.

To support this call for action, we are calling for scientists to sign the statement

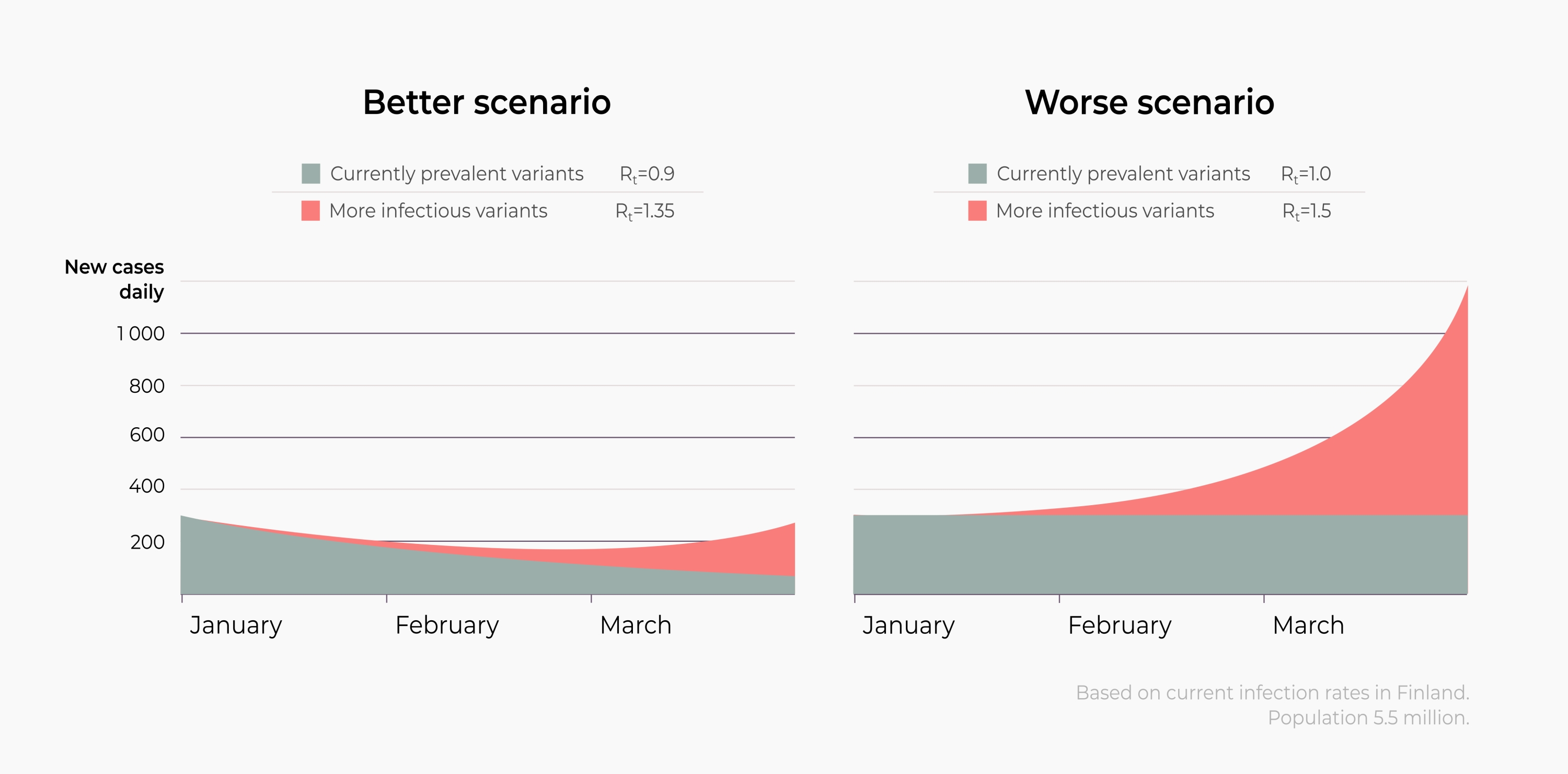

COVID-19 cases are surging across Europe. Current measures are not reducing virus spread sufficiently, and new SARS-CoV-2 variants are emerging. The B.1.1.7 and B1.351 variants, first identified in the UK and South Africa, respectively, have spread to many European countries1,2,3,4,5. Although their biological properties are yet to be characterised, epidemiological data suggest these variants have a higher transmissibility6,7. These viral properties could increase the effective reproduction number R in the population. In the case of B.1.1.7, estimates suggest R could increase from 1 to about 1.4 if there is no change in population behavior3,4. If true, many countries that have reduced R to 1 or less will be confronted with a novel wave of viral spread despite the current measures8,9. Once a more contagious variant has established itself, stabilising the number of new infections will become increasingly difficult.

Despite the availability of effective vaccines, production and vaccination will take months. Countries will have to manage high case numbers and their adverse impact for several months to come. With slowly increasing population immunity and evolutionary selection pressure on the virus, the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants will continue, potentially leading to more contagious variants and variants that might render vaccines less effective. Such variants could quickly exacerbate the crisis, long before a sufficient number of people are vaccinated. While awaiting experimental data to understand the traits of new variants, pan-European decisions have to be made, and actions have to be taken immediately to contain the spread of new variants.

If measures are not taken to prevent the spread of novel variants with selective advantages, case numbers and hospital admissions will increase. Such a surge could lead to the breakdown of health-care systems. In many countries, hospitals can no longer deliver care of the usual quality to all patients. Many intensive care units are already beyond capacity, and non-urgent procedures have been postponed for weeks or months. Delayed diagnosis and compromised care delivery for other diseases poses additional health risks not just to patients with COVID-19, but for the whole population.

Health-care professionals and other frontline workers have already been working under extreme conditions for most of the past year, and this has had a severe impact on their physical and mental health. If variants like B.1.1.7 lead to a new surge in cases, this could overwhelm the health-care force, bringing health-care systems to the breaking point. Ensuring that the burden on health care professionals is alleviated whilst safeguarding system sustainability is of critical importance. Adequate support for these crucial forces might require additional funds.

Containment and mitigation becomes more challenging with the rise of a more infectious variant. Assuming that the B.1.1.7 variant does increase R from 1 to about 1.4, then allowing it to spread without a change in people’s behavior, case numbers can be expected to double every week. Major efforts will be necessary to bring R back down to 1 or less and regain control. Acting before B.1.1.7 has spread widely means that those same major efforts could strongly reduce the number of new cases and slow down the establishment of B.1.1.7.

Europe needs to act now to delay and prevent any further spread of SARS-CoV-28,9, particularly B.1.1.7, even in the absence of final experimental data. A clear plan for immediate pan-European action and rapid establishment of public health measures needs to be formulated since new variants with increased infectivity are likely to continue to arise. We suggest possible core measures in the panel. The guiding principle is to reduce case numbers as quickly as possible as this has strong advantages for health, society and economy8,9.The joint action of all European countries will make each national and local effort more effective and impactful and thereby contributes to safeguarding public health across Europe8.

The longer restrictions last, and the less effective they become, the more depleted people’s psychological, social, and economic resources become. Where novel variants require even stricter and longer measures than existing measures, it is of utmost importance to ensure that people with particularly heavy burdens receive financial and social support, that social burdens are justly distributed, and that mental health services meet the increasing demand to cope with bereavement, isolation, loss of income, fear, alcohol and drug misuse, insomnia, and anxiety as a result of the pandemic and lockdown strategies. Contextual factors, and factors affecting risk behavior such as risk perception, must also be considered.

The core principles of action are to avoid importing new variants, to prevent their spread, and to improve molecular surveillance. The earlier and more effectively countries act, the earlier the restrictions can be relaxed. All types of measures ought to be coordinated and synchronised across Europe. Every additional reduction of contagion (i.e. of R) counts, as it reduces the necessary duration of strict measures more than proportionally.

- Achieve and maintain low case numbers with a clear prevention strategy

- Define clear targets and rekindle motivation: clearly define the targets that need to be met for measures to be lifted and explain the rationale behind them; convincingly convey that the fight against the pandemic needs a collective effort that is in the interest of every citizen; and ensure adequate social and economic support for those in need.

- Act early: implement mitigation measures before case numbers spike.

- Reduce the number of physical contacts: meet as few different people as possible; implement and improve home-office and online schooling; small, stable social bubbles, and stable groups at home and at work should be preferred over alternating contacts.

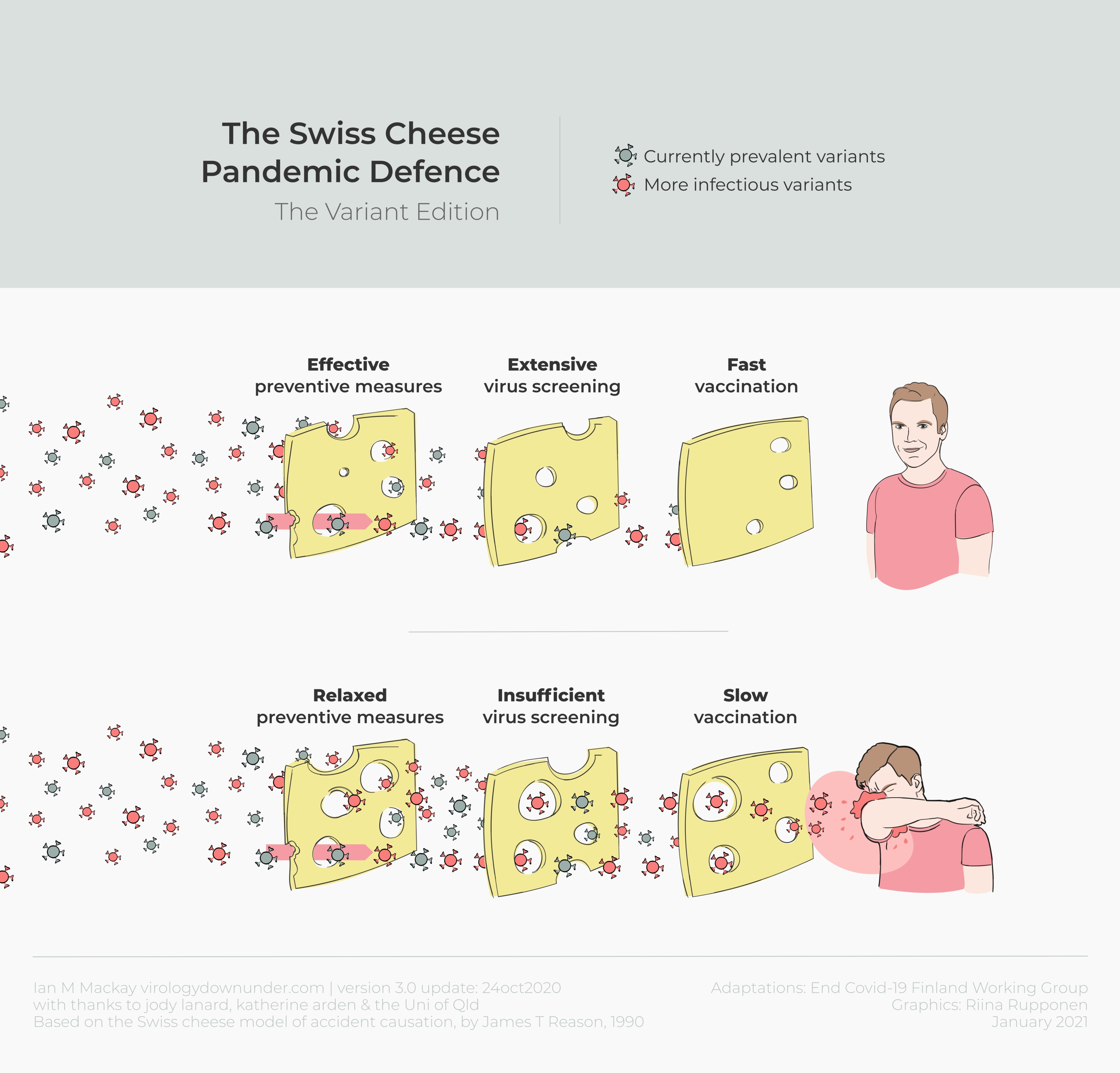

- Prevent contagion by individual measures such as physical distancing, hygiene, face masks, ventilation, and use of filters, avoiding closed and crowded spaces and staying at home when experiencing symptoms; provide FFP2 masks to those in need and to all who cannot work from home.

- Monitor the spreading of the virus and of individual variants

- Test, trace, isolate, support: enforce mandatory isolation of people with confirmed infections and encourage preventive quarantine of suspected cases; support affected individuals and families.

- Screen and test preventively: offer tests at schools and workplaces at no cost to detect outbreaks early and protect people; increase testing capacity to meet demand; use waste-water surveillance to detect local surges.

- Increase genetic sequencing and PCR-based detection of the B.1.1.7 variant, as well as other variants of SARS-CoV-210.

- Stop the virus at borders and protect the vulnerable

- Reduce travel within and across national borders, and require tests and quarantine for cross-border travellers; tests should be required 24h before travel and 7-10 days after travel; quarantine anyone arriving from countries with local COVID-19 transmission.

- Improve the protection of, and support for, the elderly and vulnerable groups; foster European exchange about successful strategies and measures to speed up the progress.

- Increase the efficacy and pace of vaccination

- Speed up vaccination: improve vaccine supply, delivery, and allocation by mutual learning and international cooperation; coordinate efforts to scale up the production of vaccines.

- Monitor infections among vaccinated people to detect potential reinfection with new variants or deficient vaccination management as soon as possible.

- Answer urgent questions through international cooperation; research ways to improve vaccination regimes to optimise logistics, or increase willingness to be vaccinated using data from multiple countries.

Further details are available in the appendix.

References

- [1] 20.12.2020, Rapid increase of a SARS-CoV-2 variant with multiple spike protein mutations observed in the United Kingdom, ECDC: Stockholm; 2020

- [2] 02.01.2021, Ny status på forekomsten af cluster B.1.1.7 i Danmark, SSI: Kopenhagen; 2021

- [3] 2020, Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data, medRxiv

- [4] 2020, Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England, medRxiv

- [5] 2021, January 8, Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out, Nature

- [6] 2021, January 8, Local area reproduction numbers and S-gene target failure, CMMID

- [7] 08.01.2021, Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01, Technical briefing document on novel SARS-CoV-2 variant; PHE: London; 2021

- [8] 2020, Calling for pan-European commitment for rapid and sustained reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infections, The Lancet

- [9] 2020, Scientific consensus on the COVID-19 pandemic: we need to act now., The Lancet, 396(10260), e71-e72

- [10] 2021, January 5, Ny test skal afsløre smitte med britisk mutation i Danmark, DR

Supplementary Information (SI)

In the following, taking an epidemiological perspective, we focus on the core principles that can slow down the spread of the virus, and noting that the aforementioned strain on public health and personal well-being need to be taken into account as well. To reduce the strain on health, society and economy, the necessary duration of strict measures should be as short as possible - which should be achieved by making them as strong and effective as possible.

It is worth stressing that our conclusions are not limited to B.1.1.7 or other variants identified to date: they apply in general whenever the emergence of new mutations challenges existing practices and strategies. Improved surveillance is necessary to detect them as early as possible, and to allow countries to prepare. In addition, experimental data to understand altered biological characteristics will always lag weeks to months behind the first identification of a new variant by genetic sequencing. Thus, wide-ranging decisions always have to be taken at a time of high uncertainty, and certainly while evidence of the real impact of new variants is still emerging. But only then proactive measures can still be effective for containment or at least deceleration of spread. The following points provide a guideline, complementary to previous ones1,8.

Achieve and maintain low case numbers, with a clear prevention strategy

- Define clear targets and rekindle motivation. The motivation and ability of many people to comply with restrictions is waning (“pandemic fatigue”), rendering any NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions) less effective. Imposing ever stricter measures puts an increasing strain on societies and economies. Therefore, governments need to strengthen public spirits by ensuring that measures are fair and consistent. This includes clearly explaining the rationales and evidence underlying these measures, and making the base for their decision-making transparent. They need to convincingly convey that the fight against the pandemic needs a collective effort that is in the interest of every citizen, and to ensure that adequate social and economic support is available for those who struggle. An important element of this strategy is to set and communicate common targets that will end the lockdown when met, instead of setting specific dates (that are then revised and extended, which compromises public morale further). People need to be re-empowered in the sense that it is in their own hands and in their own interest to comply with public health measures.

- Act early. Implement mitigation measures before case numbers spike. A preventive implementation of mitigation measures can slow down the expected increase of case numbers or even reduce current case numbers, thus alleviating the burden on the healthcare system. Especially given the interval of at least 7 days between infection and reporting of a novel case, reporting is always delayed, and mitigation measures, if taken only after case numbers start to rise, may already have reduced effectiveness. Acting promptly is therefore crucial to save lives.

Reduce the number of physical contacts. Physical contacts in all contexts bear the risk of contagions, and as the secondary attack rate of B.1.1.7 is probably 14% instead of 10% in the UK6,7, reducing contacts is even more important to slow the spread and reduce the number of new cases. This applies to all contacts at family and social gatherings, at work, at school, or in public places. The principle for everyone should thus be to meet as few different people as possible. Home-office and online schooling should be implemented whenever and wherever possible. Support for home-schooling parents should be scaled up. Group sizes should be reduced, and group members should remain the same. In all circumstances of private and professional settings, small, stable social bubbles or groups should be preferred over alternating contacts.

Public transport is ideally run with at most a fraction of seats occupied, as long as case numbers are high. The use of public transport is reduced by home-office arrangements, closing schools, and stay-at-home orders. While the risk of contagion in each type of public transport is very hard to infer, the setting - many people in a closed, crowded space - clearly bears the risk for contagion. Therefore, to protect those who cannot work from home and have to rely on public transport, public transport at peak hours should be used only by those who strongly need it and the number of vehicles should be increased. Moreover, starting times of work, retail, and schools should be staggered.

- Prevent contagion by the continuation of individual measures. By now, the transmission paths of SARS-CoV-2 are much better understood. We know that a key risk lies in ballistic drops and aerosols, with the latter accumulating suspended in air shared with an infectious individual. Therefore, the advantages and the principles of transmission prevention should be clearly communicated in easy language. Effective prevention measures are by now well known; they include physical distancing, hygiene, wearing of face masks, ventilation and use of filters, avoiding closed and crowded spaces and staying at home when experiencing symptoms. Meeting outside instead of inside can reduce the risk of contagion by a factor up to 2011. The more effective FFP2 masks should be provided at no cost to those in need, and for all employees at work.

Monitor the spreading of the virus and of individual variants

- Test, trace, isolate, support (TTIS). Detecting and breaking infection chains strongly contributes to mitigation of the spread. Here, individuals can support the health authorities, e.g. by noting down their contacts at a regular basis. Complementarily, tracing apps prove useful. Both facilitate a swift identification and quarantine of potentially infected contacts. Moreover, the knowledge gained from contact tracing improves our understanding of which contacts bear a greater risk of contagion. The necessary isolation and preventive quarantine should be clearly encouraged, enforced, and individuals should be supported. It is crucial to report case numbers, and data on hospitalization and deaths, including complementary information on local and national level, and ensure they are openly published and machine readable for scientific evaluation.

- Screen and test preventively. Given the circulation of new variants, wherever people have to meet in person, prior testing and regular screening is of even greater importance than has been the case previously. Access to tests should be facilitated, and the testing capacity has to be increased to meet the demand. At the workplace, employers should offer regular testing at no cost to their employees, ideally twice a week. Complementarily, regular, anonymous screening is helpful and important to detect outbreaks early at workplaces, schools, universities, and elsewhere. Moreover, waste-water surveillance to detect local surges and general screening is easy, anonymous, and cost efficient to implement.

- Increase sequencing and PCR-based detection of the B.1.1.7 variant. Improved surveillance allows a better prediction of case numbers and mutants. It is important to not only report case numbers but also to increase sequencing and PCR-based detection of the B.1.1.7 variant, as well as other variants of SARS-CoV-210.

Long-term lockdowns, or expansive quarantine rules, due to the burdens they impose on those affected, become increasingly ineffective and invite people to circumvent them. Therefore, with the increasing availability, accessibility and decreasing cost of rapid antigen tests, and with the first certified at-home tests becoming available, participation in non-essential activities (ranging from cultural and sports activities over restaurant visits to body-related services) should be made dependent on a negative test result not older than 24h. It is important to ensure easy access for all citizens to tests, in particular to employees at work, and that there are no other formal or informal barriers to test-taking. Policy makers should also ensure that sufficient production capacity is made available for the subsequent increased demand in tests.

Stop virus at borders and protect the vulnerable

- Reduce all travel within and across countries. Reduction of domestic and transnational travel can slow down the overall increase. Restricting mobility within a country and transnationally helps to slow down the spread of the new variant and isolate possible outbreaks of the new variant before they spread to other areas or countries. This (a) leads to a slower average increase of case numbers in the entire country, (b) reduces the number of regions requiring stricter containment measures, and (c) enables hospitals from less affected regions to support others.

- Require tests and quarantine for cross-border travelers. Preventive testing and quarantine for transnational travelers slows down the transborder spread of new variants. Therefore, two tests (at most 24 hours before travel, and 7-10 days after travel) should be required for anyone arriving from countries with local COVID-19 transmission. In addition, a strict quarantine of at least 10 days should be ordered for anyone arriving from countries with high prevalence or novel suspicious variants.

- Improve the protection of, and support for, the elderly and vulnerable groups. The best protective measure is to bring case numbers down. At high case numbers the number of undetected infections increases, and the virus is inadvertently brought to the vulnerable population8. At high case numbers, an efficient protection of the vulnerable population has not been achieved yet. In any case, protection and support plans for the vulnerable, incorporating and extending the points above, need to be improved. Here, European exchange about successful strategies and measures will speed up the progress.

Increase the efficacy and pace of the vaccination

- Speed up vaccination. B.1.1.7 has increased the need to speed up vaccination. In order to improve vaccine supply, delivery and allocation in terms of priority groups, international cooperation is urgently needed to be able to learn from each other and to implement the most effective strategies in terms of European public health and global public health security. Decision-making becomes more effective when uncertainty is reduced by combining different sources of data and data from many countries. Moreover, governments should coordinate their efforts in scaling up the production of the vaccines taking into consideration supply chains and the need to increase capacity.

- Monitor infections among vaccinated people. Vaccination is a weapon also against the current new virus variants. Initial analyses indicate that the mutations found in the novel variant do not decrease the potency of the vaccines5. However, mutations may arise against which the vaccines are less effective. This requires monitoring of infections among vaccinated people.

- Answer urgent questions through international collaboration. Many questions need answering quickly: Can we improve vaccination regimes, e.g. administer only one dose to people that have already been infected as a booster to better manage scarce resources? Would that compromise the ability to identify escape mutants? How can logistics be improved? What parameters ought to be considered in terms of allocation for effective vaccine delivery in remote and inaccessible regions? How can people best be motivated to take the vaccine and what are the best strategies to overcome vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusal?

Additional References

- [1] 20.12.2020, Rapid increase of a SARS-CoV-2 variant with multiple spike protein mutations observed in the United Kingdom, ECDC: Stockholm; 2020

- [2] 02.01.2021, Ny status på forekomsten af cluster B.1.1.7 i Danmark, SSI: Kopenhagen; 2021

- [3] 2020, Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data, medRxiv

- [4] 2020, Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England, medRxiv

- [5] 2021, January 8, Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out, Nature

- [6] 2021, January 8, Local area reproduction numbers and S-gene target failure, CMMID

- [7] 08.01.2021, Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01, Technical briefing document on novel SARS-CoV-2 variant; PHE: London; 2021

- [8] 2020, Calling for pan-European commitment for rapid and sustained reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infections, The Lancet

- [9] 2020, Scientific consensus on the COVID-19 pandemic: we need to act now., The Lancet, 396(10260), e71-e72

- [10] 2021, January 5, Ny test skal afsløre smitte med britisk mutation i Danmark, DR

- [11] 2020, Outdoor Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Viruses, a Systematic Review, The Journal of infectious diseases